Tsui Hark Rejects Idea that Hong Kong Film Industry is Dying

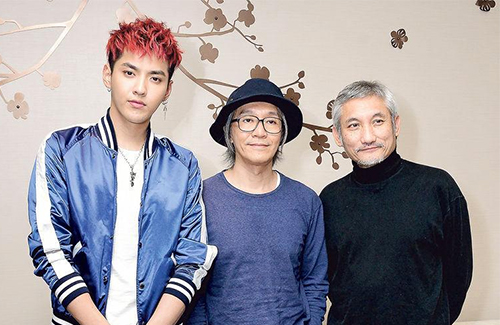

In real life, Hong Kong director Tsui Hark (徐克) is always dressed in a black coat, black pants, and black shoes. But concealed beneath this ordinary appearance are his burgeoning imagination, his penchant for putting a new spin on conventional genres, and his drive to film movies that connect with viewers. In a recent interview, Tsui shared his views on the current and future states of the Chinese movie industry.

Much noise has been made recently about the “death” of the Hong Kong film industry, especially since box office sales in the mainland Chinese film market have become notably higher. However, when asked how he feels the success of mainland Chinese movies will impact Hong Kong filmmakers and their works, Tsui responded that he does not believe in separating movies by region.

“If you separate them [by region], will you then want to split them up further, into those from Beijing, from Shanghai, and from Guangzhou?” he asked. “When filming a movie, the most important thing is whether or not the subject matter is worth sharing with viewers.”

As a result, Tsui feels that every director is “continually searching for a connection with the audience.” After all, viewers choose to see movies based not on the special effects technology or the genre, but rather the mood or mentality they need in life. “You need to develop movies with different genres,” he said. “You can’t say that one type of movie will do well at the box office and that you don’t have to develop other types. Continually repeating one type of movie will make viewers feel bored.”

To Tsui, the “death” of the Hong Kong film industry is not an independent discussion topic. “I always talk about Chinese movies, and Chinese movies include Hong Kong and Taiwanese movies,” he explained. “If the film market in one place isn’t good, that doesn’t mean the movies from that place have died. The development of movies is always a process of highs and lows.

“When filmmakers create movies, they change in itself according to the changes of the new era. Perhaps sometimes the process of this change takes a longer time, but in the end, you can still create works that reach the audience more closely.”

Since his youth, Tsui has been a fan of the wuxia genre, which he sees as a distinguishing characteristic of Chinese film and a tradition that should be maintained. Although he feels that China has many traditional subject matters that deserve to be explored and developed, the recent trend toward realistic subject matter has drawn him back to martial arts films.

“It would be a pity if nobody did this subject anymore,” Tsui said. “I actually like a lot of different types of movies, and when I’m filming a martial arts movie, I will often film a few movies dealing with other subject material, thus exploring the room for development in Chinese film. But recently, it seems as though fewer people are doing wuxia movies, so I’m starting to film them again.”

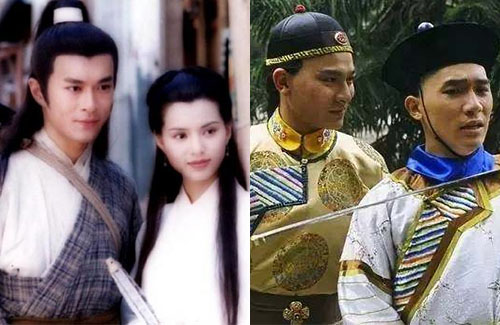

Tsui’s martial arts films are such a cornerstone in the Chinese movie industry that his depictions of characters like Dongfang Bubai have become permanently etched in the minds of viewers. However, he never thought that his interpretations would be considered “classics.”

“To a director or a filmmaker, the most important thing is that you like some story or some subject, and that you want to film it in the best way, in your style, in order to let viewers enjoy your mood and feelings about this story. You can’t force viewers to remember a role – you can only wish for that to happen. To give a simple example, when Li Bai was writing his poems, he never thought that, after thousands of years, we would still be reading his poetry.”

For Tsui, the focal point is still the filmmaker’s connection with his or her audience. When asked about the “new” era of wuxia, as depicted in movies like Wong Kar Wai’s (王家衛) The Grandmaster <一代宗師>, Tsui shared that martial arts films have experienced several stages of change since the 1950s. “Every change has a source and a course of events,” he said, “and these can’t be separated from the relevant era and the demands of the viewers.”

Source: QQ.com

This article is written by Joanna for JayneStars.com.

No offense but in his hands, maybe.

Its been dying close to 10 years.

That’s a slow death, maybe got cure? Definitely not in the hands of Tsui “So dark, can’t see a thing!” Hark or Wong “Pose, wind, sulk, no script, 6 years in the making” Kar Wai.

I really feel that your hate is somewhat ungrounded for Tsui Hark and WKW. They both have unique direction that defines a part of HK cinema.

Besides, arthouse films (what WKW is renowned for) is characterized by minimal dialogue and more art direction/sets/choreography-heavy.

If we have even to question whether or not the industry is dying, then it really is dying.

I’m just saying.

I think HK films still have hope, only it shld reduce those lousy comedy, focus more on proper storyline movie. It is all those lousy comedy type films (meaningless) that drag its standard down. I love stephan chow’s comedy though, it shld be a comedy with good story, not just mou lei tou comedy…

I loved Peking Opera Blues – I tried to do my homework assignment on it. I didn’t really like or understand Chinese Ghost Story.

Cleo – still the undisputed champion of jaynestars

Tsui Hark’s A Chinese Ghost Story is a golden classic…..even remakes with those exaggerated cgi moments cannot convince otherwise.

Tsui Hark is one of the most talented Director around. I love his movies.

Love Tsui Hark. He’s my favourite director. He’s always trying new things.

Many don’t like his later movies like ‘Legend of Zu’ and ‘Seven Swords’ but I like them. ‘Seven Swords’ could have been better if it was not cut short to accommodate cinema time.

Seven Swords was weird. I remember pestering my pops to buy it when I was here and when I watched it I was like “what the fk? What happened?!”